-40%

PENDANT BOLIVIA JEWELRY 1654 8 REALES PIRATE GOLD COINS CAPITANA SHIPWRECK COB

$ 1029.59

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Bolivia 8 Reales 1654 "Captain Shipwreck" PendantPirate Gold Coins Shipwreck Jewelry Treasures

PENDANT BOLIVIA JEWELRY 1654 8 REALES PIRATE GOLD COINS SHIPWRECK TREASURE CAPITANA (russ)

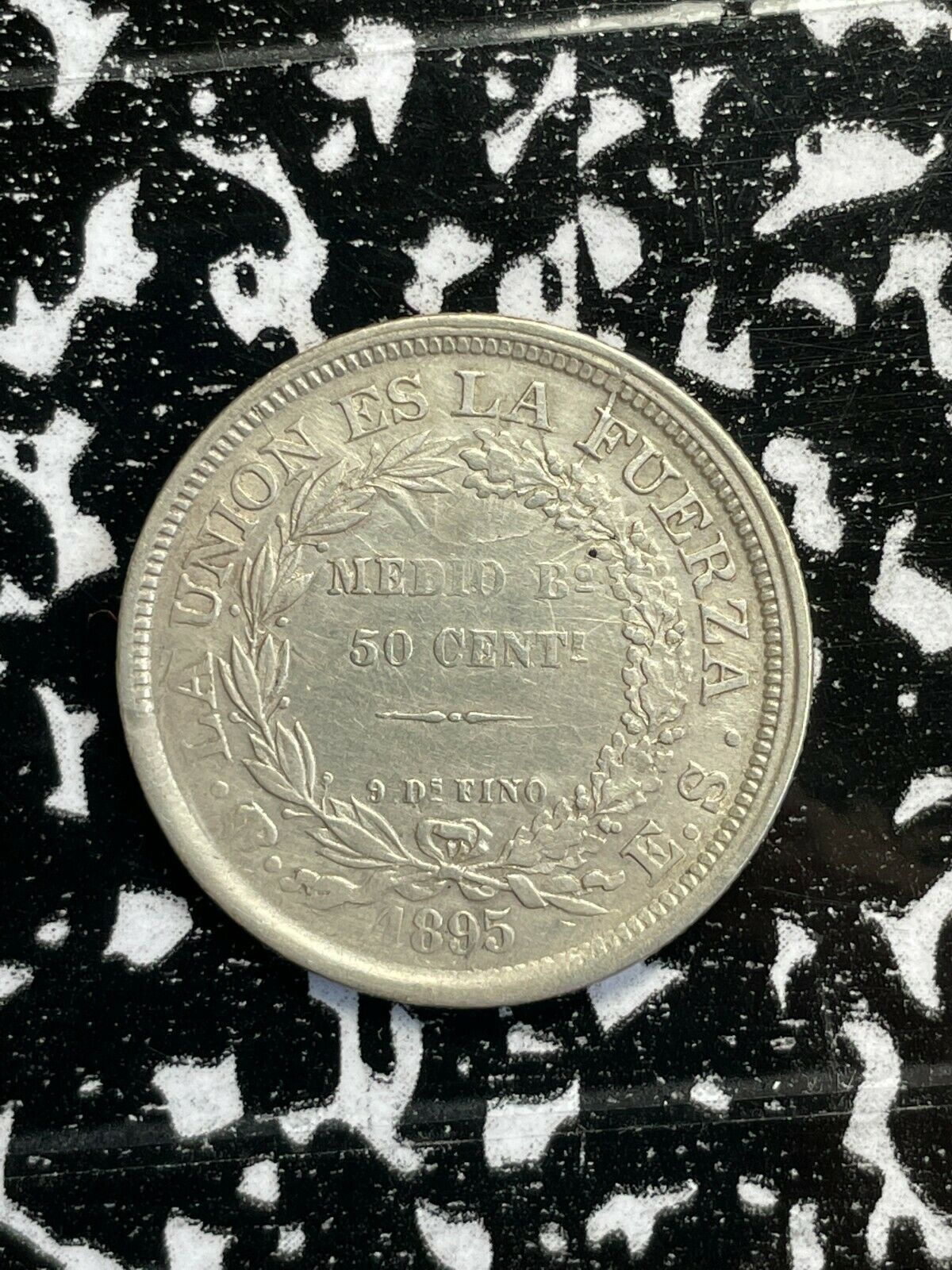

This Authentic DATED 1654 8 Reales set in a Silver and Gold Bezel with a GOLD GALLEON emblem on the reverse was found on the Shipwreck CAPITANA of 1654! Total weight 25.78. The Mint mark “P” Potosi is visible as well as the Assayer and most importantly, the DATE 1654! This piece is way above average, displaying the FULL CROSS and Lions & Castles, as well as the Tressure and Crown (not to mention, even the Legends are partially legible: HISPANIRUM). Topped off with a GOLD Bail for you to place your Gold or Silver Chain through. READ Below about the Capitana of 1654.

On October 18, 1654, the 1200-ton La Capitana I Jesus Maria de la Limpia Conception weighed anchor in Callao, Lima's port city, and Captain de Sossa ordered a course set north for Panama. Built in Guayaquil in 1644, La Capitana measured 130 feet—more than 40 feet longer than any Spanish ship on the high seas. The largest ship built in the Americas, the barrel-shaped galleon was twice the size of the famous Atocha (sunk 1622) discovered by treasure hunters in 1985 near Key West.

On this day, La Capitana carried in her timbered hold a fortune worth a king's ransom in treasure—taxes collected over a two-year period, valuable coins from the counterfeiting scandal that rocked Potosi, and millions of pesos in contraband not listed on the ship's manifest. Not counting the contraband, La Capita-no's cargo in- cluded 2212 silver bars, 216 chests of silver coins, and 22 crates of silver goblets, pitchers, trays, and candelabra.

Dangerously overloaded with treasure and six-hundred passengers, La Capitana rode deep in the water, her keel was twenty-four feet below the surface. So heavily laden was La Capitana that her escort ship, the Almiranta, had to lower its sails so as not to overtake her laboring charge. It took the two ships a week to inch up the coast to the Bay of Guayaquil.

At 11 o'clock on the night of October 26,1654, under a full moon, the bow look-out aboard La Capitana noticed land. A navigational error had brought the ship perilously close to shore. The pilot ordered the cannon fired—once, and then again—to alert the Almiranta's Captain Alonzo Montero following behind. He then ordered the sails tightened. La Capitana heeled slowly, turning laboriously across the wind and heaving toward the open sea. It was then that the ship's keel slammed repeatedly against an underwater reef. The heavy blows took their toll. The rudder broke free and the La Capitana was out of control.

Frantically, the crew tried to turn the stricken ship away from the rocks and drop anchor, their work hampered by the clutter of boxes and crates of unregistered and personal cargo. Amidst the chaos and confusion, sailors struggled to disentangle and anchor able. This cost precious time. With the ship crashing against the rocks below, the crew finally dropped two anchors just as the ship heaved. The anchors tethered La Capitana perilously close to the reef.

That night, the exhausted crew toiled ceaselessly at the pumps while all who could pitched in, bailing with jars or anything that lay close at hand. As dawn broke on October 27, the situation grew even more dire. Rising water defied the pumps. Water in the lower hold rose nearly five feet and continued to rise. Captain de Sossa stayed with his ship, lurching about his cabin naked and drunk. A ship’s officer later testified that he saw his captain nude in his cabin consuming the hallucinatory and addictive paraguas plant (a narcotic mushroom). Speaking to the court, the ship’s officer opined that de Sossa expected to die and had therefore decided to meet his maker in a state of euphoria (Shipwreck, by Dave Horner). At length, Captain de Sossa roused himself long enough to dispatch Don Francisco Tello in the gondola with orders to row the Almiranta and bring prompt help to unload the royal treasure. While they waited, sailors aboard La Capitana cut an opening through the deck and struggled to haul the heavy silver ingots up from the hold and stake them on deck, ready for rescue, But no boats came. Don Francisco Tello returned with word from the Almiranta: Expect no help for the Almiranta, it too, had scraped rocks and feared the worst. As Don Francisco Tello Delivered this news, Catain de Sossa turned to see the Almiranta hoist her sailed and move off. This craven deed so infuriated La Capitana’s crew that Captain de Sossa could barely retain them.

Water gushing through planks in the damaged hull rose to fourteen palms and churned ominously in the holds. Treasure chests littered the deck, but there was no help in sight. His ship in grave peril, Captain de Sossa held council with the ship’s officers. It was then de Sossa ordered the mast cut to make rafts and so transport the silver to shore. But as the captain and soldiers left the ship, panic broke out. The crew ignored orders to stay aboard. In desperation, crew and passengers leapt into the sea. Grasping planks, cables, masts, and even chicken boxes, they left their posts and pumps and made for shore.

Twenty passangers jumped over the side and swam towards shore, their pockets stuff with gold, silver, and other valuables. All died.

By three o’clock on the afternoon of the 27th of October, de Sossa returned to his ship. All appeared lost. In desperation, the captain, with the remnants of his crew, hoisted the sprit-sail and maneuvered the sinking ship away from the reef and through a channel to beach in shallow waters. Here, the crippled La Capitana came to ground in four and a half fathoms.

Before La Capitana sank out of sight, more rafts were hastinly thrown together to save as much rreasure as possible. Chopping through the deck, Captain de Sossa sought volunteers to dive into the hold and salvage what they could.

For King Philip IV of Spain, the wreck of La Capitana was a crushing disaster. Spain, teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, required vast sums to pay for European Wars.

The Treasure of La Capitana lay on the sea floor as surviors debated measures to retrieve at least a portion of the priceless cargo. Every day for four months, divers brought in from Panama dove the waters off the small town of Chanduy. In all, they salvaged some 3,339,751 pesos a treasure larger than the 2212 silver bars noted on the ship’s manifest.

But with time, changes swept over Europe. The sinking of La Capitana was the beginning of the end of Spain as a major power, and off Chanduy on the coast of Ecuador, currents shifted the sands. Little by little, the silver coins, bronze cannonballs, and other booty that had not been salvaged when La Capitana went down disappeared, buried under layers of silt. Soon, even the location of La Capitana slipped out of memory.

k

k